Cuba: Realm of possibility

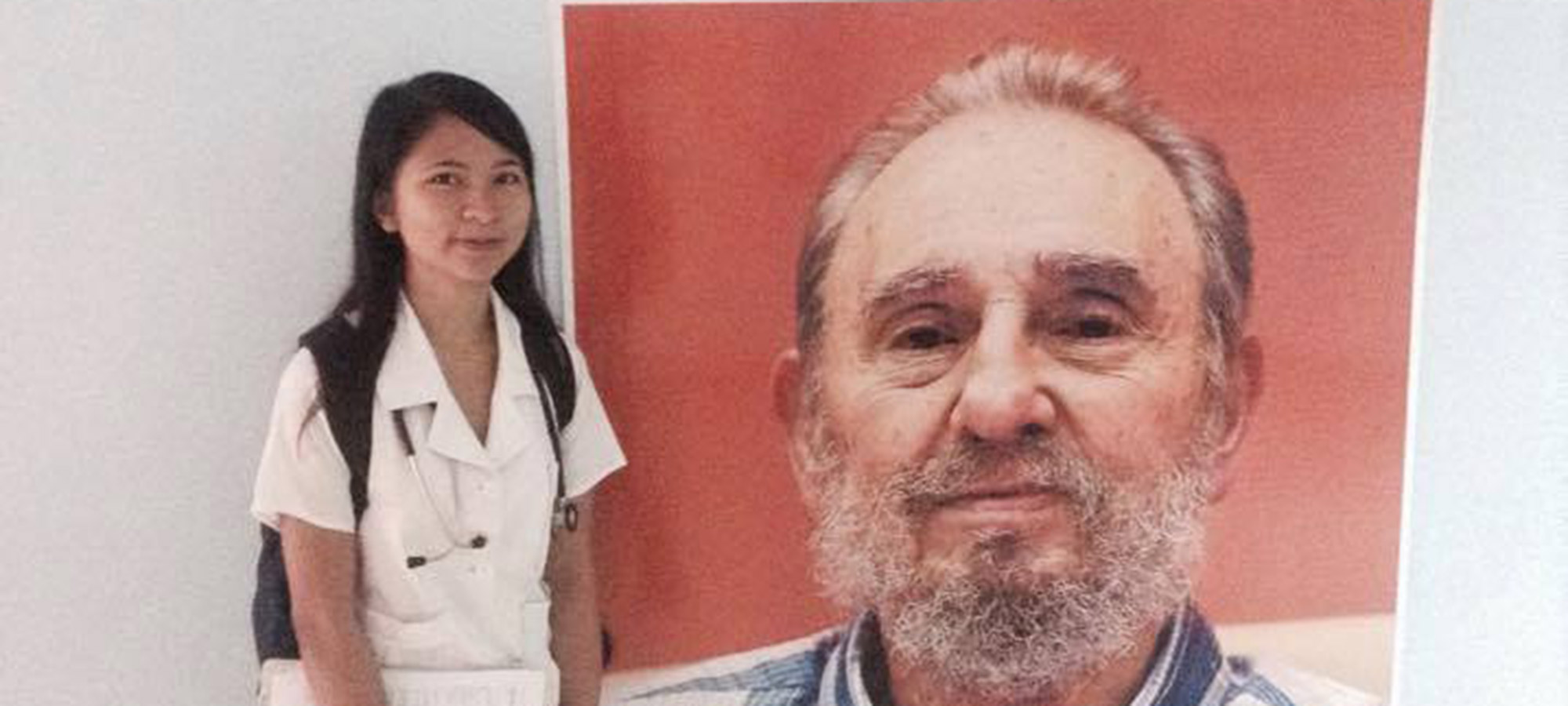

A Filipino medical student studing in Havana writes about the Cuban health care system.

Integral, Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina

The phrase“Sí se puede” is perhaps one of the most quoted ones in Cuban society. In bold, red letters, it is often painted in walls, printed in posters and emphasized constantly in the speeches by officials in different ceremonies and activities. Roughly translated to “Yes, it is possible,” it is a phrase that has perhaps become the mantra of Cubans in their daily lives, in the pursuit of any endeavor. It is a phrase that the Cubans have undoubtedly applied in numerous ways to their health care system.

As such, when asked, “Is it possible for a country with third world conditions and alas, with a Gross Domestic Product even less than other third world countries to provide universal health care to its people? Is it possible at all that this country could consistently have an infant mortality rate of less than 5 per 1000 births since 2008, to have a doctor-habitant ratio of about 1:200, comparable with those of first-world countries?,” I have seen the Cubans answer with a resounding “Sí se puede.”

Cubans and temporary residents like us, the students here, enjoy the benefits of universal health care. We can ask the doctor as many questions about a sudden abdominal pain or a skin rash, get a blood test or a chest X-ray without ever having to worry about the bill. Procedures ranging from simple ones like asthma treatment to more complicated ones like an appendectomy, the laparoscopic removal of a kidney, cancer treatment or open heart surgery are without charge. For students, we can get a prescription for a drug and get it from the school pharmacy, whether it is a vitamin supplement or an antibiotic—all of which is for free.

As my History and Medicine professor often says, the idea of not being able to go to a hospital or receive health care because a person does not have money is rather a foreign concept for Cubans. If Cubans do not want to go to the hospital, it is more so because they are afraid of getting an injection, or being diagnosed with a disease. Never because they are afraid of the bill.

Access granted

The Cuban health care system, it seems, does not leave room for excuses for Cubans not to seek medical care when necessary. It is so structured such that it would be both economically and geographically accessible. The health care system is divided into the national, provincial and municipal levels. At the municipal level, they have what is called a policlínico. A policlínico is open for 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It is like a small hospital, complete with doctors and nurses, providing different medical services like physical therapy and dental care.

Integral, Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina

To each policlínico, there are at least five consultorios that correspond to it. Each consultorio or clinic has what is known as the “equipo básico de salud” or the basic health team, comprised of a doctor and a nurse. Each health team is assigned to a certain community within a municipality, allowing as much doctor-patient interaction as possible. Together, the policlínicos and the consultorios comprise the primary level of health care. As medical students, we visit the consultorios once every two weeks and the policlínicos three to five times every semester, as part of our training to interact with patients and learn as much from the practical experiences of the doctors and nurses that work there.

In the consultorio I was assigned to in my first year of medical school, the doctor knew which among her patients were pregnant and needed a prenatal checkup, which ones had just given birth and had babies whose weights and heights needed to be monitored, which ones were hypertensive and needed to have their blood pressure checked regularly. The doctor even knew which family had a house that was caught on fire five years ago. The doctor was not only someone with a white lab coat that visited the community every now and then; the doctor was part of the community. She had the trust of its members–an essential component in the healing process.

Just before taking a patient’s blood pressure or radial pulse, the doctor in my current consultorio would emphasize how there is a necessity to touch the patients, to interact with them, to not be distant with them, to treat them not merely in terms of signs, symptoms and diseases, but as whole human beings. These whole human beings perhaps have marital problems, are faced with financial constraints or are going through an emotional or familial crises—details the doctor would never find out without gaining the patient’s trust. A hypertensive patient may have high blood pressure because of high salt intake or obesity, but she may also have a controlling husband, or an alcoholic son who gives her constant stress—factors no prescription of antihypertensive drugs could address and are best dealt with family therapy.

Obstacle upon obstacle

Ideal as these conditions might seem, their health care system is not without its flaws. After all, this is a country which has been subjected under an economic embargo by the United States of America (US) for more than 50 years now.

Due to the embargo, Cuba has lost more than US$6 Billion. The extraterritorial character of the embargo’s terms has given the US power to put sanctions on countries which have trade relations with Cuba, making the export and import of products very difficult. Moreover, Cuba has limited internet access and still uses 1950s vintage cars as one of their main forms of public transport. The embargo has repercussions that have echoed through every aspect of Cuban society, and their health care system has not been exempt.

Due to the limited internet access, recent articles in medical journals are not easy to obtain. Certain medicines and medical equipment like pacemakers, those manufactured in the US, are not always available. They would have to be bought from a third country, making the drugs and equipment even more expensive than necessary. Medical equipment is not always up to date. There would sometimes be a shortage of certain drugs and supplements. For instance, though Vitamin C tablets can be freely obtained from the school pharmacy, they would sometimes be out of stock. Certain medical supplies may be bought from the stores in the month of May but by the month of July, it would be very difficult to find them again.

In these conditions of dire lack, resourcefulness and creativity are of the essence. Cubans are constantly compelled to find ways to do what is necessary in spite of these limitations. While the embargo could easily have caused them to forgo universal health care altogether, the Cubans have decided to take the path of resistance.

Integral, Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina

Better than cure

Instead of giving in to the economic limitations, to the lack of funds, causing the resources needed to treat patients to be limited, Cubans have chosen to emphasize prevention. Cubans believe in a saying that “if people are falling off a cliff, it is more humane and cheaper to place a fence at the edge than to build a hospital perfectly provided with medical personnel and equipment at the bottom.” (Si la gente se está cayendo por un precipicio, es más humano y más barato colocar una defensa o cerca en la altura, que construir un hospital perfectamente dotado en personal y material en el fondo.)

From birth until over 60 years old, Cubans receive vaccines for up to 12 diseases, of which some are proudly Cuban produced, like the vaccine for bacterial meningitis (AM-BC). Patients suspected of having communicable diseases such as dengue, malaria or cholera are immediately isolated. As such, a fever is always a cause for concern. The detection of even a slight decrease of platelet count, a possible symptom of dengue, is never taken lightly. To prevent the spread of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, the use of condoms is constantly promoted through posters and TV commercials.

To promote a healthy body, exercise and sports are highly encouraged. There are groups of senior citizens exercising in parks in the mornings, children and teenagers playing either football or baseball in the afternoons. Recreational parks complete with gym equipment are practically scattered throughout the whole country.

Of all the preventive measures, perhaps, the most effective one is education. In 1959, before the triumph of the revolution, 23.6 percent of Cubans were illiterate due to the high cost of education. Fifty-five years later, from Day Care until graduate school, education is free. As such, Cuba has a highly educated populace and consequently, a highly health-conscious one. We have patients who go to a consultorio or a policlinico just to have their blood pressure taken. We have patients knowing the symptoms of a disease and the medicines they need even before a doctor could tell them.

Free health care and education, however, come with a price. This price has been consistently paid by the Cubans. Such achievements were attained in what could only be the harshest of conditions, conditions for which the moral rewards have been abundant but the economic ones are rather very scarce. Doctors here are not associated with the affluence that comes with the medical profession as they are in other countries. They do not necessarily have fancy cars or well-furnished houses. Yet, most of them still show up to work on time, attend to their patients and teach classes in the most animated way possible.

It is one thing to dedicate oneself to excellence and service knowing that there are economic rewards to be gained from it and another to do so out of principle and the genuine belief in the improvement of the human condition. For pursuing this belief, Cuba has been severely punished with the embargo. Yet, what we can learn from the Cuban experience is that, even in the unlikeliest circumstances, achieving goals can be made possible given the political will and the unity of the people. The realm of possibility could be vast if we believe it to be so. Within this realm, we could find a better world, a world where no child, woman or man would ever need to die from perfectly preventable and treatable diseases.

References:

Rodríguez JL. Estrategia del desarrollo económico en Cuba. Ciudad de la Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales; 1990

Álvarez Sintes R. Medicina General Integral Vol. 1: Salud y medicina. Ciudad de la Habana: ECIMED;2008