Dear Meg,

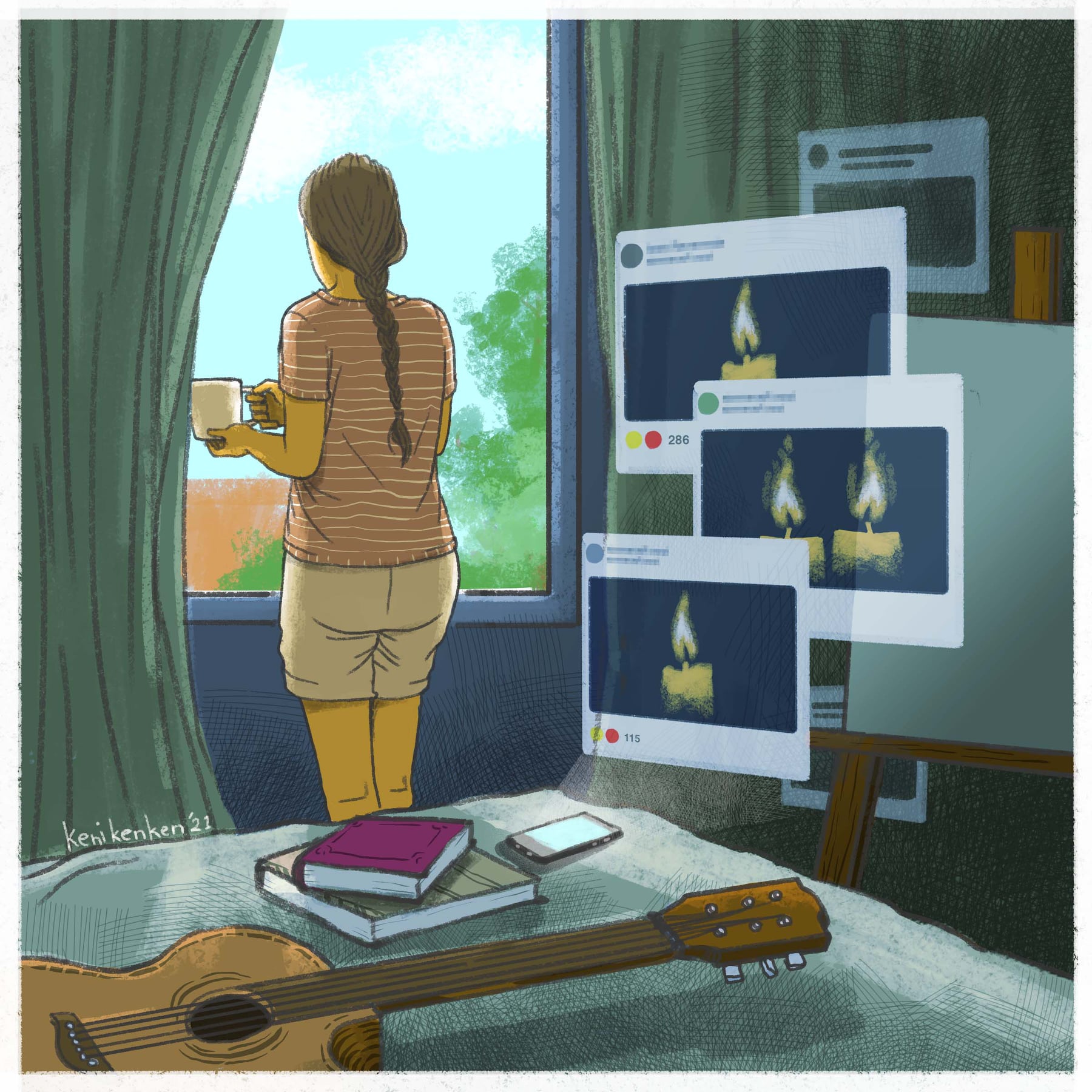

It’s hard to open social media these days – it’s just sad news everywhere. I lost many teachers and relatives to Covid over the past months. And seeing how the government is handling the situation just gives me no hope.

I’m an artist but I’ve been feeling so unmotivated to create or to even connect with friends. Can you tell me – is there still anything to look forward to?

H

Dear H,

I hear you, and I’m very sorry for your loss.

Months ago, while trying to make sense of these disconcerting times myself, I reached for a book in my shelf titled Gilead, by Marilynne Robinson. In it an old preacher writes to his very young son – he had him late in life – with the intent of introducing himself, perhaps leaving some fatherly wisdom along the way, knowing they’re living on borrowed time.

I knew what I was looking for when I opened its pages again. Between musings on faith and race, Robinson offers an eloquent meditation on life and the nature of being. Her John Ames is a most thoughtful man who likes to read and write and to walk the streets at night, relishing the neighborhood’s sights and sounds. He speaks of the banal and the existential in the same breath: their family cat, his strange grandfather, grace, and the miracle that is water:

“I saw a bubble float past my window, fat and wobbly and ripening towards that dragonfly blue they turn just before they burst. So I looked down at the yard and there you were, you and your mother, blowing bubbles at the cat, such a barrage of them that the poor beast was beside herself at the glut of opportunity. She was actually leaping in the air, our insouciant Soapy! Some of the bubbles drifted up through the branches, even above the trees. You were too intent on the cat to see the celestial consequences of your worldly endeavours. They were very lovely. Your mother is wearing her blue dress and you are wearing your red shirt and you were kneeling on the ground together with Soapy between and that effulgence of bubbles rising, and so much laughter. Ah, this life, this world.”

I guess we could say John Ames knew how to pay attention. Confronted with the tragic, terrifying fact of his mortality, he committed to being deeply aware of the present moment, savoring each sensation. In that sense, we’re a bit like him amid this pandemic: forced to stare death in the face – though perhaps more brutally, in our case – with nothing to look forward to.

I wish it weren’t so, and that spreading excitement is as easy as sprinkling pixie dust. I could, for instance, list down things that delight me and hope you’ll feel the same. But we get thrilled only by what we hold dear, and something tells me you’ve already given this much thought. You probably have many things you would like to experience again, and what torments you is not knowing whether they can still happen.

If the future looks bleak, maybe our comfort can be found right here, right now. Maybe the goal is to feel grounded in today, and deal with tomorrow when it comes.

Crudely, this is what the practice of mindfulness is about: the absolute acceptance of the present moment. By absolute we mean having no categories, no judgment – only a keen awareness of what is.

Mindfulness also introduces us to a kind of happiness other than this intense, overpowering, uncontainable high. The thing about it is if we didn’t know any better, anything else feels sad and low.

Through mindfulness, we learn about equanimity – the ability to be even-keeled, calm and composed, no matter the circumstances. As a shifu once shared in a meditation class, once you’ve become mindful, you can find happiness even while washing the dishes. I can’t say I’m an expert at it by now (I still hate washing the dishes), but I’ve experienced those moments she was talking about, and I wish that feeling for you.

Most of mindfulness training, in fact, is about keeping still. We listen to our body, and observe how we respond to different things. We sit with our discomfort and determine, then embrace, the bigger truths behind them. I have, for example, written before that being an artist means being more attuned to the aches and pains of the world. Maybe, this is what you’re going through.

I can see how unnerving it is to be unable to create, but I want to say this doesn’t make you less of an artist. I would even argue that you’re feeling this way precisely because you are one; you perceive the world with intuition, which tells you something’s wrong with it. We look to the likes of you to tell us about being human, and if this is how it is in a time of grief and suffering, then so be it. Your empty canvas is our collective truth.

Which is not to say it will be like this forever. Once you get to know yourself some more, and be in touch with your feelings of anguish, fear, even rage, you’ll learn how to express them well – perhaps even through your art – or keep them at bay. Very soon, you’ll discover things that will make you excited about life again, and put back the twinkle in your eyes, as Robinson writes.

“The twinkling of an eye. That is the most wonderful expression. I’ve thought from time to time it was the best thing in life, that little incandescence you see in people when the charm of a thing strikes them, or the humor of it.”

Wishing you a calm, peaceful week. The future can wait.

Meg

#therapy #psychology #art #creatives #mentalhealth #mentalhealthph