Reading the Masses in the 2022 Elections

The motifs of protest vote, resentment towards the system, and even electoral insurgency have become commonplace, even cliche, among political analysts in the country, since the electoral victories of Joseph Estrada in 1998, Aquino in 2010 and Duterte in 2016. Such claims, however, must be examined in the context of the actual campaigns waged by the winning candidates and the elites during the election.

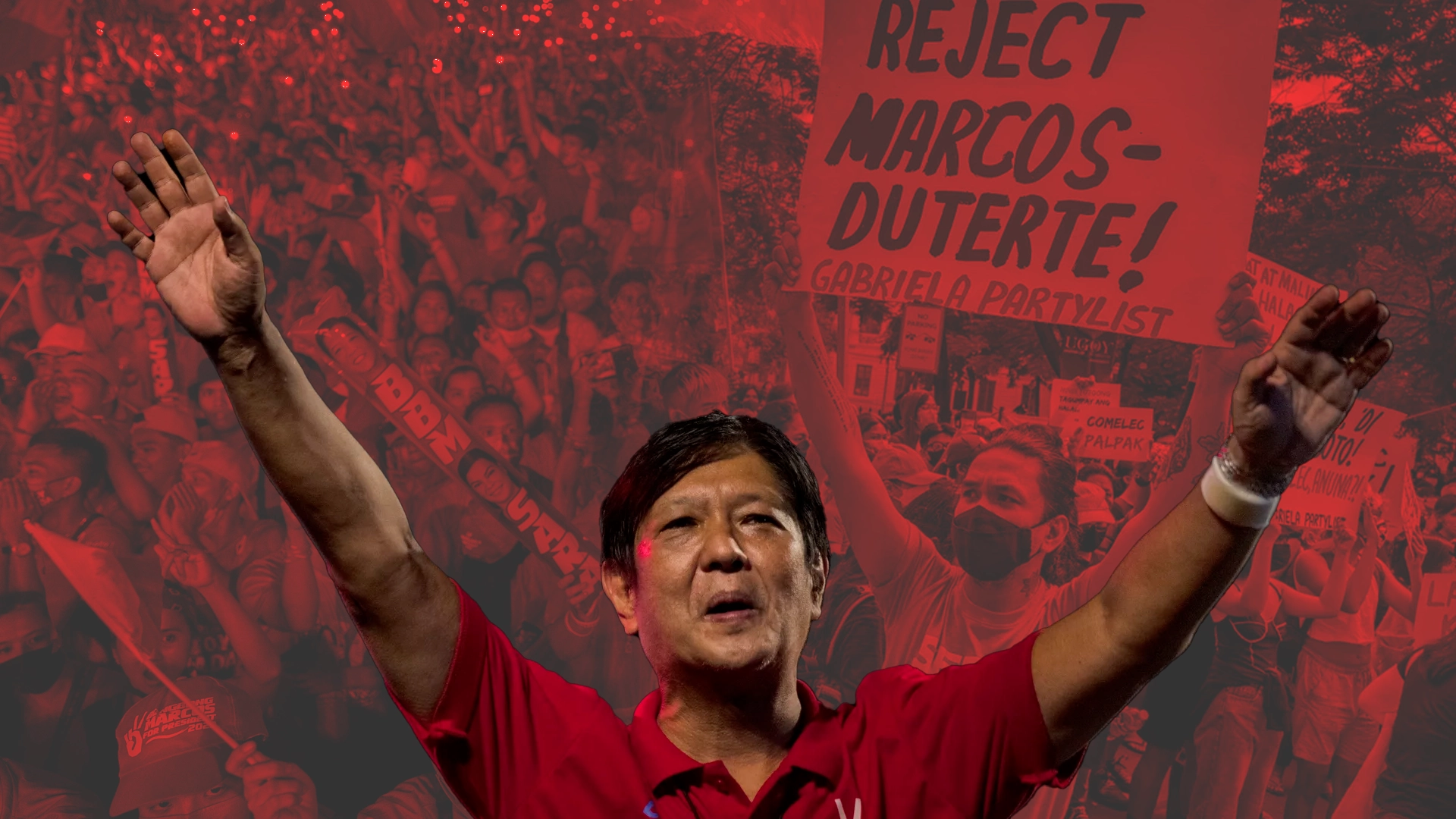

The 2022 presidential win of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr broke many electoral records set after the 1986 Edsa People Power uprising. The number and percentage of votes that he received are the highest, and he has become the first president to be elected by a majority, not a plurality, of votes. His lead against the nearest competitor is also the biggest, and he got more votes than the topnotcher in the Senate race.

These are no mean feats, of course, as Marcos Jr is the son of the long-standing face of dictatorship, corruption and economic decline in the Philippines who was ousted through a two million-people strong uprising and belongs to a family long considered a pariah in Philippine society. The victory of Marcos Jr and his running mate Sara Duterte, daughter of Rodrigo Duterte, a president that rivalled the older Marcos in many respects, has made the 2022 elections historically significant for the Filipino people.

These facts have forced commentators to talk about the majority of the Filipino people, those who belong to the lower classes, or the Filipino masses, in relation to the elections. Progressives most especially are having conversations about the masses, as they must. As cultural critic Edel E. Garcellano writes, “Reading the masses… is reading the revolution and reading the revolution is reading the praxiology of our times.”

Sociologist, activist, legislator and 2022 vice-presidential candidate Walden Bello recognizes the malfunctioning of voting machines, vote-buying funded by billions of pesos, and online disinformation campaign as having “played a role in the election result.” At the same time, he sees the number and percentage of votes garnered by Marcos as “simply too massive to attribute solely” to those factors. The Marcos-Duterte disinformation campaign, according to him, had a “receptive audience.”

Bello says that while the votes for Marcos in 2022 and also Duterte in 2016 are “probably inchoate and diffuse at the level of conscious motivation,” these constitute “largely a protest vote” against “the persistence of gross inequality,” “extreme poverty… and poverty, broadly defined,” “the loss of decent jobs and livelihoods,” joblessness and the push to go abroad, and the “rotten public transport system.” It is fueled by the “resentment against the Edsa status quo.”

Herbert Docena and Maria Khristine Alvarez, Sociology professor and urban geographer respectively, agree. They state that “In the final analysis, what enabled Bongbong to win the presidency was not simply the machinations of his powerful family, but a strong current of resentment – directed at the liberals, unharnessed by the left – that the Marcoses could not have conjured on their own. Inside their trove of lies was a simple message which many believed to be true: that life did not improve after the People Power Revolution.”

Further analyses should be made and studies undertaken but the picture that emerged even during the campaign season — and which Bello and Docena-Alvarez set aside, as if they’re the only ones thinking right — would point to minimal yields in favor of their claims.

How could we arrive at the beliefs that animated the Marcos-Duterte vote? Karl Marx, in a foundational quote of historical materialism, states that “We do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life-process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life-process.” According to him, “In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth,… we ascend from earth to heaven.”

Seeking to provide an “explanation backed up by some empirical validity or analytic plausibility,” the Center for People Empowerment in Governance or CenPEG cites the following factors that contributed to the Marcos-Duterte win: the size and strength of “election bailiwicks rooted in regional-linguistic identities and loyalties,” continuing popularity of Duterte, “systematic campaign of disinformation and historical revisionism, especially in social media,” division in the opposition, “huge financial and organizational resources of the Marcos-Duterte team especially with the support of other powerful families and oligarchs,” and problem-riddled automated electoral system.

All these should be seen in the context of Duterte’s regime-long consolidation of power and attacks against all actual and even potential opposition forces. The massive resources at the Marcos-Duterte team’s disposal enabled it to buy votes in various ways. Electoral fraud cannot also be discounted, at the very least as an explanation for the enormous lead.

Did all these factors contain resentment at the liberals and the Edsa system? To what extent? Further analyses should be made and studies undertaken but the picture that emerged even during the campaign season — and which Bello and Docena-Alvarez set aside, as if they’re the only ones thinking right — would point to minimal yields in favor of their claims.

Claims about the nature of the votes for Marcos-Duterte should be examined in relation to the actual conduct of their electoral campaign, and not simply read off as something of a post-facto surprise. Philippine elections, after all, are elite-dominated and are closely observed by different sectors of society.

If the huge vote for Marcos is, as Bello and Docena-Alvarez claim, a resentment-fueled protest vote, then it should be reflected in at least a vocal section of his voters. The rational kernel that they claim to have extracted from the mass of votes should at least be audible to many observers.

It can immediately be conceded that resentment at the liberals — the Dilawans, the Aquino political dynasty, the Liberal Party — can be heard among Marcos-Duterte voters. Saying that they are expressing resentment at the Edsa system and the country’s structural problems, however, would be too much. Their main criticism of the opposition presidential candidate is that she is supposedly stupid, not even elitist. Still, one wonders if resentment at the liberals is the dominant belief among these voters.

Another approach would be to examine the messages of the Marcos-Duterte campaign. Dominant in electoral campaigns are the voices of the political elites who are trying to woo voters. It would be absurd to think that the masses are expressing their protest through their vote when the political elites’ campaign simply do not contain, or instigate, such a protest.

As everyone knows during the campaign, Marcos was not presenting a platform and making promises to the public, was not discussing his track record or accomplishments, and was avoiding all questions from the dominant big-capitalist media. He was just repeating his campaign theme — “Unity” — over and over, which is so narrow and empty that he often sounded stupid.

Docena and Alvarez say that Marcos “merely presented different iterations of a single vow: that he would follow Duterte by keeping the yellows out of power.” The truth is that the candidate was so playing safe and so incoherent that this vow is not a prominent aspect of his messaging, if it was made at all. The authors claim that “the candidate fostered a strange kinship between himself and the masses.” The truth has been stated by someone on Twitter: unlike most presidential candidates, Marcos made no attempt to present himself as coming from the masses. He cannot claim to come from poverty; in fact, he will give away his family’s wealth. He is a Marcos after all, not a masa.

Contrast Marcos 2022 with Duterte 2016: “To gather popular support…, Duterte made audacious – and, in hindsight, deceptive – promises to the electorate: a ‘stop’ to contractual employment among workers, to land-use conversion which adversely affects farmers, to large-scale mining that destroys the environment and drives away indigenous peoples from their land, among others. He… promised free college education…” He also promised to stand up to foreign powers encroaching on the country’s territory.

With these promises as bases, this author made the observation that “Duterte, in effect, became the first post-Edsa big league presidentiable to promise policies anathema to neoliberalism and the neoliberal consensus of post-Edsa regimes.” While the 2016 Duterte campaign can lay claim to having harnessed the masses’ resentment against the so-called “Edsa system” and the then-ruling liberals, making a similar claim for the 2022 Marcos campaign would need more evidence and explanation.

We know, of course, that while Marcos was silent in the area of track record and platform, his propaganda machinery was going overdrive in other areas. Nicole Curato, another sociologist, presents a more concrete description of the messages in what she calls “cultural battles” that led to the Marcoses’ return to Malacañang.

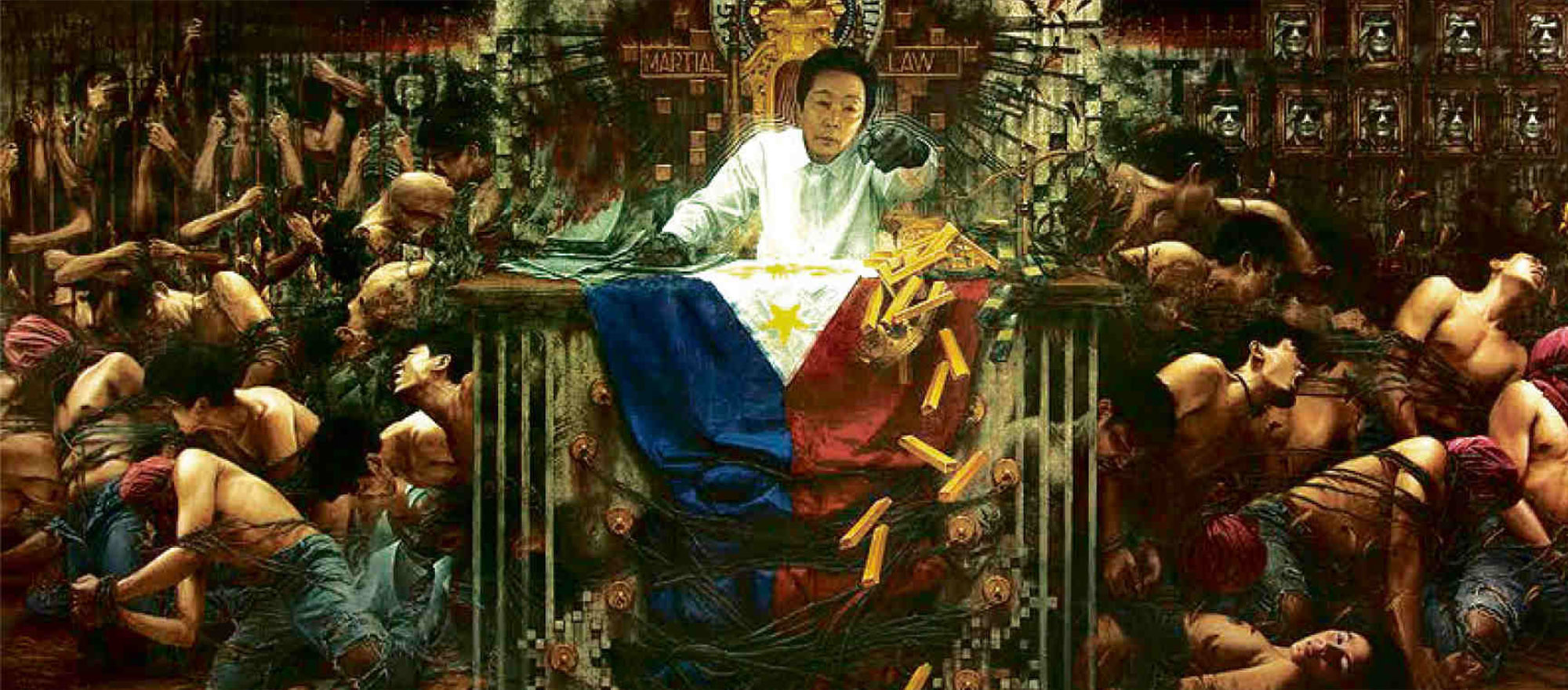

According to her, the Marcoses have been “glamorized” for many years. YouTube channels that glorify the dictator’s infrastructure projects have increased. The supposed legitimate sources of the family’s wealth have been explained in viral TikTok videos. Marcos and his family have been portrayed as relatable and admirable. All these were happening as “opposition voices” were being “constantly harassed on various platforms by an army of trolls” and the opposition candidate was being portrayed as “dumb and incoherent.”

A Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism story on disinformation presents the following themes: the Marcos era was a “Golden Age” for the Philippines, during which many important structures that provide social services were constructed. Marcos did not plunder the country, had many legitimate sources of wealth, and planned to distribute his wealth to Filipinos. The Marcoses are celebrities who look elegant and are loving towards each other — here, availing of what Curato elsewhere called “influencer culture of good vibes and toxic positivity.” They have been denied the presidency twice.

It would appear from the foregoing that the vote for Marcos-Duterte is primarily a vote for a supposedly better candidate and only secondarily a vote against a supposedly inferior candidate — much less a vote against the ruling social and economic system. It of course highlights the rottenness of the ruling system in the country — but saying this is different from ascribing this view to the masses themselves, as Bello and Docena-Alvarez do.

Docena and Alvarez sought to ground their, and Bello’s, “popular resentment, protest vote” analysis of the results of the 2022 elections into a narrative of middle-class support for liberals from 1986 until the Noynoy Aquino presidency, which started in 2010, and then for the anti-liberal Duterte in 2016.

There is so much that this narrative fails to take into account. One, the middle class, which at the time was supportive of liberals, became critical of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo because of the 2005 Hello Garci, the 2007 NBN-ZTE and other controversies. Arroyo ended her term with the lowest approval ratings in recent history. Two, Aquino ended his term with a decent level of support from the middle classes, as anyone who observed his regime closely could say.

Three, Docena and Alvarez trace middle-class disillusionment with the liberals to the neoliberal economic policies implemented by ruling regimes who profess allegiance to liberal ideals. They admit, however, that Duterte continued these policies, even as he “ridiculed liberal shibboleths” and ramped up repression of all forms of opposition. So how do they explain Duterte’s enduring popularity with the middle class and his ability to transfer this popularity to Marcos Jr?

Four, how could the masses be angry at the system and not be angry at its current representative and defender, the Duterte regime, which is by many indicators one of the worst presidencies in recent history?

The authors make it appear that parallel to ruling regimes’ implementation of neoliberal economic policies is a growing wave of popular resentment which finally brought Marcos to the presidency. They problematically label the system standing behind these regimes as “the Edsa system,” in effect denigrating the popular uprising that ousted the Marcos dictatorship, perhaps to the applause of the latter’s champions.

The crises of the ruling system in the Philippines — neocolonial and semifeudal according to the dominant section of the Philippine Left — are reflected more immediately in the crises faced by the ruling regimes than in people’s sentiment, whether towards the ruling regime or the ruling system. How ruling regimes handle these crises affect people’s sentiment towards them. That is why, for example, the Aquino and Duterte regimes were able to end their terms with high popularity ratings.

To deny the agency of ruling regimes in handling crises and therefore posit an unmediated relation between the ruling system and people’s sentiment is to fall into vulgar and crude Marxism or leftism — or to a plainly romantic-left view of the masses. It is also to ignore history in favor of what one likes to believe — which, in this case, even provides ballast to anti-liberal propaganda and to mythmaking for the Marcos-Duterte win.

While Bello and Docena-Alvarez recognize, by mentioning and then setting aside, other factors that brought about the Marcos-Duterte victory, the emphasis of their analyses privilege the masses’ agency over the determination of structures in the Philippine electoral and political system. This is contrary to honest, even bourgeois, social-science studies that highlight the elites’ control over these systems and show how the agency exercised by the masses within these systems is determined — perhaps even “overdetermined” — and limited by such structures.

They are rare in the Philippines: self-professed leftists who affirm the capacity of bourgeois elections to give voice to the masses. They can be overly critical of the liberal and Left opposition but apparently not of Philippine elections — which, even ordinary people will say, do not bring about real change in the country.

There is no need to rehearse here the well-known problems that characterize elections in the Philippines’ neocolonial democracy, from patronage politics to violence to electoral fraud. Bello and Docena-Alvarez devalue these explanations for the results of the 2022 elections. They are rare in the Philippines: self-professed leftists who affirm the capacity of bourgeois elections to give voice to the masses. They can be overly critical of the liberal and Left opposition but apparently not of Philippine elections — which, even ordinary people will say, do not bring about real change in the country.

In this sense, Bello and Docena-Alvarez’ analysis is analogous to that of political analyst and columnist Richard Heydarian, who also sets aside long-standing problems in Philippine elections and simplistically attributes the results of the election to a single mindset. According to him, election results show “a torrent of unmediated rage against decades of dysfunctional democracy” and that Filipinos “have had enough of half-baked reforms and half-hearted liberal slogans. They want decisive leadership.”

Worse, the authors make it appear that, in choosing Marcos-Duterte, the masses harbor progressive reasons — that what appears as class-in-itself, to borrow Marx’s famous distinction, is actually class-for-itself. They depict the election of the son and daughter of fascist dictators as the expression of the revolutionary consciousness of the masses amidst the weakness of the Left. Not only are these claims false and hilarious, they are as such also not good guides to activist action.

On the basis of their uncritical analysis of elections in the Philippines and with the direction of pushing for heightened Left participation in elections, Docena and Alvarez present many criticisms of the Philippine Left. The one-sided obsession of these criticisms with elections could be shown by contextualizing these within the Left’s principles.

The Philippine Left of all progressive formations in the country has been building its “own autonomous power base” although it does not gear that base fully for participation in what it calls “reactionary elections.” It has been harnessing the masses’ resentment towards the system, reflected in their resentment towards regimes and regimes’ policies, precisely by building its organized strength. It is also very clear in its strategy and vision of revolutionary victory — unlike other progressive formations in the Philippines that simply glide from one elite-dominated election to the next.

Advancing a “compelling alternative to elite rule” and “a radical opposition to the Marcos settlement” cannot be measured by participation in elections alone, or mainly. The “mainstream” is not in the elite-dominated elections, but in the struggles faced and waged by the masses in the grassroots. What is curious is that Docena and Alvarez want to widen the gap between the Left and the liberals in the country by pitting them repeatedly against each other — as if the patently authoritarian-fascist factions of the elites are not the ones in power and benefit from their approach. They ignore the clear evidence that the Left has not always supported liberals in elections.

Docena and Alvarez’ criticisms of the Philippine Left dovetail with those of Josua Mata, leader of Sentro, which describes itself as “a progressive multi-sector trade union alliance” and is close to social-democratic group Akbayan. Compatible with the assumption that Philippine elections are a level playing field, Mata’s assessment shifts its focus from the elections and the Duterte regime to the Philippine Left. He says that the Left “is in crisis for quite some time now,” “has failed to put forward a convincing political alternative,” and “is not able to translate… vision into workable programmes that resonate among the people.”

Despite the Left’s silence about Sentro, and after an election in which the Left allied with the elite opposition, with which Sentro is also aligned, Mata surprisingly criticizes the Left for being “sectarian.” He says that sectarianism is a “symptom” of the problems stated above, but it is clear that he means that this is a cause. He is in effect saying that the broad Philippine Left cannot carry out what he thinks is the correct strategy because the biggest Left formation refuses to cooperate with other progressive groups. This is most irresponsible, because leftists are supposed to gain strength on the basis of correct strategies. You have the winning strategy? Then show its correctness in practice, don’t delay implementation and then blame other Left formations for supposed problems caused by the strategy’s non-implementation.

Mata accuses the Philippine Left of “Stalinism” — which here does not mean the Trotskyist canard about supporting elites, but something more Cold War: supporting dictators, as in Duterte. Mata harps on the Left’s alliance with Duterte but is silent when it comes to the Left’s dogged opposition to the Duterte regime, despite countless deaths and imprisonment. Mata’s group, on the other hand, has been largely silent in the fight against the regime, and has not been at the receiving end of state repression.

The labor leader traces the labor movement’s problems to the lack of “a deep sense of democracy,” something so high-falutin compared to the real, more humdrum, reason recognized by many: repression in the form of retrenchment of workers who try to unionize. He blames a supposedly ingrained Left culture instead of blaming the attacks carried out by capitalists and the government.

Mata makes it appear that Left tactics during elections — setting criteria for politicians who can be endorsed, presenting a labor agenda to politicians, and asking politicians to sign a covenant — are practiced only by Sentro, contrary to evidence. Worse, despite his left phrasemongering, Mata’s strategy is still directed at bourgeois elections: “By developing the labour vote, workers should be able to capture state power that we can then use to hasten social transformation.”

For his part, Bello criticizes both the Left’s mass movement and election work. He has, after all, not said anything positive about the Philippine Left since the 1986 Edsa uprising, which saw it committing a serious tactical error. It is but predictable that he would be more caustic in his criticisms of the Left in the wake of the Marcos restoration and the Left’s failures in the 2022 elections. He appears to be losing his head amidst what he sees as a defeat of the Left.

He trashes the Philippine Left’s work from 1986 to present. Honest and close observers, however, would say that there were many ups and downs during that period, both in the armed and parliamentary struggle, including the electoral struggle. The Philippine Left remains the biggest formation in the broad progressive movement in the country, has continued to fight despite severe government repression, and is still considered by the government as its main enemy. Despite many years of attacks and black propaganda and the rigging of the elections, it has actually increased its votes, even as it lost partylist seats, in 2022.

While Bello says that the Marcoses and Dutertes were able to harness the masses’ resentment against everything from poverty to policies imposed by the IMF, World Bank and the WTO, the Left has “been reduced to a voice yapping at the failures and abuses of successive administrations,” considered as “irrelevant or, worse, a nuisance by large sectors of the population.” His masses are a curious absurdity: they have progressive sentiments, gained apparently on their own, are supportive of fascists, and are leery of the Left. In analyzing the Marcos-Duterte victory, he imagines a representative of the politically-advanced section of the masses; in analyzing the Left, he conjures a representative of the backward sections — who are never happy with the Left or any politics at all, and whose views are never a good basis for organizing.

Leftists themselves would be the first to admit: there is much to study, change, improve, unlearn, dismantle, surmount in order to improve the Left’s work, especially in the face of the Duterte and Marcos regimes. Bello’s criticisms, however, are too distant, slapdash and outright malicious to be taken as starting points for such improvement. He does not even accept severe state repression as a reason for the weaknesses of the Left. He is the know-it-all you don’t want sitting in your meeting, whose notion of accepting defeat is self-laceration unwarranted by facts, and whose analysis never leads to practical solutions and is an extension of the enemy’s attacks.

Faced with the Marcos-Duterte victory, one would expect Bello, Docena-Alvarez and even Mata to present self-criticisms of their sections of the broad Philippine Left. While some of their criticisms of the Left can be read as self-criticisms as well, it is clear that they are still targeting the national-democratic Left, which is so dominant in the Philippine Left it can stand for that category. The Left has worked so hard to fight the Duterte regime and the Marcos-Duterte victory, yet it ends up being criticized for the latter. Mata’s group has worked for the isolation of the Left in the alliance with the elite opposition, while Bello and Docena-Alvarez’ group has refused to cast its lot with the elite opposition most capable of defeating the Marcos-Duterte tandem; both have not risen to the challenge of setting aside differences and forging unity in order to defeat the tandem.

The Leftist groups to which Bello, Docena-Alvarez and Mata belong are the ones that have steadily decreased in strength since the early 1990s — except when Akbayan served as an adjunct of the Aquino regime.

The Leftist groups to which Bello, Docena-Alvarez and Mata belong are the ones that have steadily decreased in strength since the early 1990s — except when Akbayan served as an adjunct of the Aquino regime. They have wasted many generations of young activists who have had the misfortune of joining organizations that simply could not consolidate them. They are silent throughout the reign of previous regimes, except for some moments of “staging a presence” in which they mouth leftist generalities about crises, system, socialism and alternatives. They are not the main targets of state repression, but are undependable in at least expressing solidarity with those who are. They are more active in releasing commentaries, especially in international left-wing publications, often attacking the Philippine Left, than in grassroots organizing and politics.

The motifs of protest vote, resentment towards the system, and even electoral insurgency have become commonplace, even cliche, among political analysts in the country, since the electoral victories of Joseph Estrada in 1998, Aquino in 2010 and Duterte in 2016. Such claims, however, must be examined in the context of the actual campaigns waged by the winning candidates and the elites during the election. Bello criticizes old ways of thinking and acting as the causes of the Left’s decline. Faced with the new realities that created, and are created by, the Marcos-Duterte victory, it is indeed time to critically examine old modes of thinking, even by political analysts who claim to be breaking away from these.

17 June 2022

Thanks to M. Beltran, J. Lumanog, R. Mallari, and R. Villegas for reading and commenting on the previous drafts of this essay.