Introduction | Dear Meg: Advice on life, love, and the struggle

So here we have it: an advice column that affirms the value of the individual and connects this to the necessity of collective struggle for a better way of collectively organizing our collective lives; that presents basic leftist principles and the big picture of society even as it dishes out many practical advice; and that nurtures the broken, the beaten, and the damned at the same time that it delivers them some hard truths, mostly about expectations rendered unrealistic by the ruling social system and mindsets that are proving to be debilitating, so that they can carry on in the struggle.

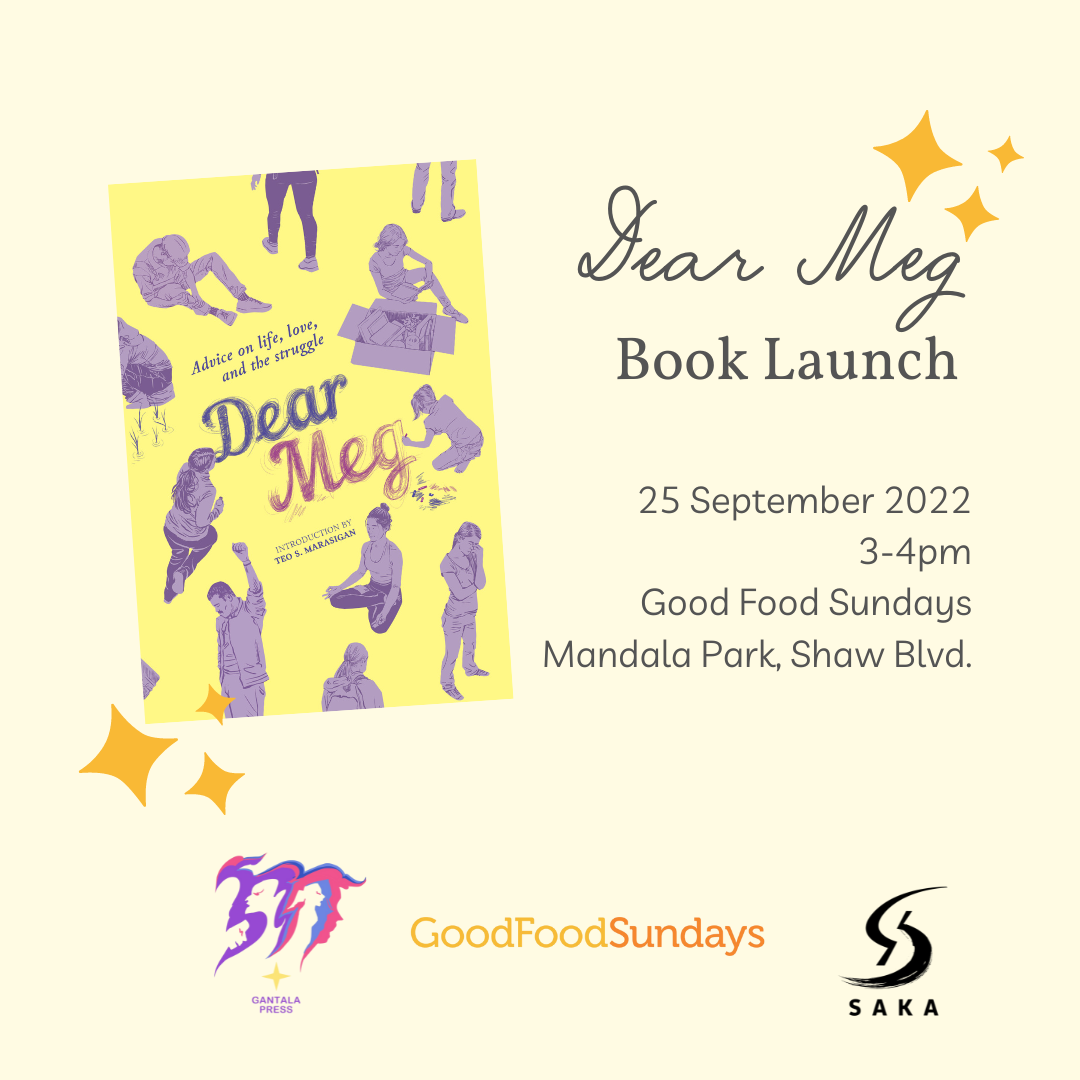

Dear Meg: Advice on life, love, and the struggle is a collection of advice columns written by a psychologist and fellow activist named “Meg,” and published under the title “Dear Meg” in progressive news magazine Pinoy Weekly (dot org) and in a Facebook Page bearing the column’s name.

Meg started the column in July 2020 and has continued to write it to this day. As an advice column for the said readers, “Dear Meg” is intimately connected with its immediate social and political context, the effects of which are most palpable in the questions that Meg finds herself asked.

It is easy to invoke two proper names that constitute that context – the COVID-19 pandemic and the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, which many describe, for many good reasons, as neocolonial, fascist, and cronyist. Such a social, political, and economic context could only bring out and heighten various emotions, feelings, and even types of affect from the target and actual readers of the column.

Still, the existence and thriving of an advice column written by an activist, in response to questions coming from comrades, allies, sympathizers, and ordinary people who espouse basic leftist views, and read and shared by the latter, cannot be explained by its social context alone.

The popularity of “Dear Meg” is also explained by the continuing vitality of the Philippine Left despite the numerous blows that the latter received from successive regimes, and despite the latter’s tactical weaknesses and setbacks. It can also be attributed to the existence in the Philippines of one of the longest-running Communist-led armed insurgencies in the world and of a vibrant anti-imperialist and democratic mass movement that has ousted two presidents and has served as a thorn in the side of all presidents.

“Dear Meg” is in demand largely because of the emergence, also brought about in various ways by people’s movements in the country, of a new generation of politically-committed and socially-concerned Filipinos, many of whom were and still are being politicized through social media and starting out as “woke.” Living in an increasingly dark and desperate time, their enlightenment and growing ranks are themselves a source of hope for the nation – a hope that must still be nurtured, strengthened, and organized in a general sense.

**

On the one hand, the writings of Marx and Engels generally dwell on the economic and political structures of society, and focus on the collectives that are classes as agents in making society and history. The same can be said of the writings of Lenin and Stalin. Many Marxist and progressive intellectuals in the West have made these observations, and have added that Marxism does not have as comprehensive an understanding of individuals and subjectivity as it does of structures and collectives.

On the other hand, Maoism is the variant of Marxism or Marxism-Leninism that has been dominant in the Philippines, and the writings of Mao Zedong contain more passages pertaining to the revolutionary individual, and collective, compared with the writings of the previous “great teachers.”

At the same time, we live in a period, in both the world and the Philippines, when there has emerged a deeper and more widespread appreciation of issues surrounding the individual, that can be observed across generations – in society at large and even among activists and revolutionaries. It is commonly observed that members of the younger generations called, rightly or wrongly, as “millennials” and Gen Z are more conscious of their individual rights and their personal space, and have a richer vocabulary for describing the state of their mental health and sexual identities. There has also been, for years now, ongoing conversations about mental health problems, sexual relations, and similar issues, in the activist and revolutionary movement.

Even as it highlighted that “we are in the same boat,” the COVID-19 pandemic, and especially under the Duterte regime, has brought to the fore the individual and various issues related to it. It has worsened mental health problems and has inadvertently highlighted these even as it restricted collective and face-to-face ways of handling these.

There are many ways that the activist and revolutionary movements in the country are responding to this situation, and “Dear Meg” is one of those. By saying this, we are putting nuance to a possible misunderstanding of the idea of “movement response” – as having organizational imprimatur or as decreed from the top. No, “Dear Meg” is neither of these. It is a “movement response” in the sense that it is the contribution of a concerned movement member who is acting on what she perceives as a need, seeking to respond to that need based on broadly shared principles, open to criticisms and suggestions for improvement, and receiving a generally warm response. This is not to say, of course, that “Dear Meg” always faithfully reflects movement positions on various issues.

The movement response that is “Dear Meg” is humble, tentative, and tactical, taking the form that it did – an advice column, not a theoretical treatise on subjectivity and structure, individual, and society. It is a generally leftist response to concrete issues and problems that draw from currently available intellectual and emotional resources.

In short, if “Dear Meg” was not invented, it would have to be invented – in response to a social context where issues pertaining to the individual have become increasingly known, in order to bring individuals – its readers – closer to an understanding of the progressive movement’s handling of such issues, and in order ultimately that individuals be able to come together to confront and change the dominant economic and political structures in society.

So here we have it: an advice column that affirms the value of the individual and connects this to the necessity of collective struggle for a better way of collectively organizing our collective lives; that presents basic leftist principles and the big picture of society even as it dishes out many practical advice; and that nurtures the broken, the beaten, and the damned at the same time that it delivers them some hard truths, mostly about expectations rendered unrealistic by the ruling social system and mindsets that are proving to be debilitating, so that they can carry on in the struggle.

It is amazing that while it recognizes the dire objective conditions and the difficulties that these impose on the subjective factor, “Dear Meg” always ends up giving readers an empowering, agitational, and hopeful sense that things can still be done and society can still be changed. And it talks directly not only to those in need of its advice, but encourages ordinary readers to talk to the same people, and educates them on how to do it.

Although the necessity of its invention can confidently be said, the particular form which this “movement response” took is a pleasant surprise. While Meg recognizes the influence of Marxism and “emancipatory psychology,” as well as learnings from people whom she calls comrades, mentors, authors and the masses, a plurality of influences are at play in her writings. “Dear Meg” directly quotes, surprisingly, more from African-American writer James Baldwin than from Filipino Communist revolutionary Jose Maria Sison – though perhaps the latter would approve of “Dear Meg.”

**

“Be concerned with the well-being of the masses,” said Mao Zedong, in one of his many famous aphorisms that Filipino activists and revolutionaries take to heart. At a time when socially-conscious and activist Filipinos are looking inside themselves even as they look to change the Philippines and the world, they need not only financial assistance, food, medical services, among others. They also need what one would be wrong to call “moral support” in contrast with “material support.” They need words of advice, words of comfort, healing talk, fighting talk, ideas that give a sense of direction – all of which become material in their hearts, minds, and actions.

Meeting these needs is one of the tasks being carried out by many guerrilla fighters in the countryside and activists in many locations and communities. In the crucial online and print space during the COVID-19 pandemic and under the Duterte regime, “Dear Meg” took up the task of fulfilling some of those needs. And readers – activists, activist supporters, soon-to-be activists; old and new – are being helped and are being thankful.

We certainly hope that Meg is just starting. Even so, we follow her lead in appreciating what deserves to be appreciated. Thank you, Gantala, for publishing “Dear Meg” as a book and enabling it to reach more people. And of course, thank you, Meg.