From Bicutan to Mamasapano

On media coverage of the Moro struggle, from Bicutan siege to Mamasapano massacre.

I remember that day, March 14, 2005, well.

They called it the “Bicutan siege.” It was an incident that has mostly been forgotten today, but it casts a long shadow in our country. That day, six inmates from Camp Bagong Diwa in Taguig City got hold of handguns, shot at their guards and held the Special Intensive Care Area (SICA) hostage for more than a day. These inmates were alleged members of the bandit group Abu Sayyaf. They demanded that their cases be expedited in courts, and that their human rights be respected.

I covered that incident. On the evening of March 13, 2005, I went to the Bicutan jail and interviewed a few government officials who were negotiating with the hostage-takers. Among them were then-Rep. Mujiv Hataman and Sen. Alan Peter Cayetano—curiously, two of today’s cast of characters in the Senate’s Mamasapano hearings.

The independent and alternative media extensively reported on this. I remember being so angry with the dominant media I lost a few days of sleep. It was mostly cheering on Reyes and company for a job well done as the inmates’ horror stories about the siege slowly reached us. The detainees’ side of the story were told through their families who were able to talk to their loved ones after days, maybe weeks, of being held incommunicado.

The inmates told a most horrific tale: the SAF members shot at many detainees point-blank. Among those killed was 75-year-old Hadji Ahmad Upao, a bedridden detainee suffering from Alzheimers. The inmates said that Kosovo indeed led the hostage-taking, but Global and Robot were not part of it. Their stories were affirmed by the Commission on Human Rights, under then-Chairperson Purificacion Quisumbing, which came out with a report recommending that charges be filed against Reyes and police officials who sanctioned the assault.

Fast forward to February 2015, almost a month ago, when I went with a fact-finding team to Mamasapano, Maguindanao to cover the aftermath of the January 25 carnage. That town saw some SAF commandos themselves reportedly killed in ways that recall that of the Bicutan siege of 2005. In its aftermath, the public—rightly so—overwhelmingly offered sympathy with the wives and loved ones left behind by the fallen 44 police commandos. The public raged against the President’s continuing lack of remorse, even as facts bear out his direct responsibility in and for the incident.

The Moro deaths in that cramped prison compound in Bicutan in 2005 may be smaller—exactly half of that of Mamasapano. But the horrific circumstances of those deaths should have been enough to enrage the public with the same intensity as that of Mamasapano. Except, of course, for the fact that the victims were Moros and Muslims. Except that they were—in the government’s and the mainstream media’s view—terrorists.

It’s called Islamophobia, of course, and it goes back a long way in our country. Spanish and then American colonial rulers saw Moros furiously fighting against invasions. Because they resisted, they were called “savages” by these foreign invaders. Exactly 109 years ago this month, about a thousand Moro men, women and children were massacred by American forces in Bud Dajo in Jolo island. Because they were mere “savages”, US President Theodor Roosevelt even commended US Major General Leonard Wood for the massacre, which he called a “brilliant feat of arms.”

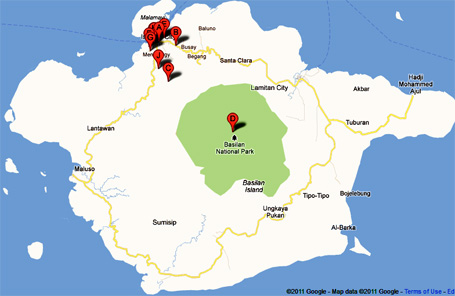

I covered a few of these similarly brilliant feats of arms. One such feat was the arrest of more than a hundred supposed terrorists in Basilan, Jolo and Tawi-tawi in July 2001. Then-President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declared a “state of lawlessness and rebellion” in those provinces during that time, following a series of kidnappings perpetrated by Abu Sayyaf. Many of those arrested without warrant were brought to Camp Bagong Diwa in Bicutan, Taguig. They were ordinary farmers and fisherfolk. In the aftermath of the Bicutan siege in 2005, this is what I wrote back then about them:

“I visited Bagong Diwa in 2002, and talked with some of these detainees and their relatives. They claim to be innocent of the charges. In some cases, authorities (mostly Christian) were so confused with the Muslim names that they arrested individuals whose names merely resembled that of wanted (Abu Sayyaf) members. For example, if the military had a Halim Alih in their list, and they encountered an Alih Halim, the latter (would be arrested).

“The arrests were practically arbitrary. Some had slight resemblance to a wanted terrorist. A 60-year-old father was accompanying his arrested son when he himself was arrested and accused of being a terrorist. One detainee-slash-‘Abu Sayyaf member’ was 76 years old at the time of his arrest. He’s now 80.

“Most of these detainees were arrested without warrant, tortured, detained miles away from home (their families had to shell out a fortune to be able to visit them in jail), their cases prolonged. A great injustice was done to them.”

Later that year, November 2001, another story unfolded in Moroland: that of Nur Misuari, erstwhile Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao governor, who renewed his armed struggle against “imperial Manila” after government troops attacked a Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) camp and killed at least five MNLF fighters. This happened despite the supposed effectivity of the 1996 Final Peace Agreement between MNLF and the Philippine government.

In April 2002, I joined a fact-finding mission to Jolo island to investigate reported human rights abuses by government troops after Misuari’s rebellion. Here is part of what I wrote in the Philippine Collegian about that mission:

“On October 2001, the villagers related, government troops under a certain Major Maningo attacked an MNLF camp, murdering five (5) disarmed MNLF members and wounding three (3). After which, the troops shelled a village mosque, killing an MNLF member who sought sanctuary there. The troops then fired at a pile of Qur’ans (the Muslim holy book).

“According to the villagers’ account, these soldiers proceeded to run over with their chemite tanks the nearby civilian houses. Those houses they did not destroy, they looted. Goats, chickens, cows, expensive Muslim dresses, appliances, even doors and roofs were carted away. The villagers’ claim of looting is an interesting one. Before our interviews with the residents, someone from Jolo told us that once in a while he would spot a military truck in town filled with tables, appliances, goats, chickens. On our way back to Zamboanga City, I saw a navy boat docked on the pier, stuffed with long tables, appliances, and narra doors…

“We interviewed the wounded, the widows, the terrorized children – they saw what the government troops did. And this was only in one barrio. In Talipao alone, there were 49 more barrios that were reportedly victimized the way Upper Tiis was. There are 18 municipalities in Sulu.

“The reports of aerial strafing targeting civilian areas were confirmed by our experience in these areas. Last April 21, one (fact-finding mission) team conducting interviews and ocular inspections in Indanan was strafed with machine guns by two helicopter gunships. Luckily, some were able to hide in a civilian foxhole while others used a balete (banyan) tree for cover.”

In many ways, the details of 2001’s Jolo incidents parallel that of last month’s Mamasapano incident. The attack in Talipao, after all, was also ostensibly against Abu Sayyaf members. Government troops also thought nothing of violating not just a ceasefire agreement, but a final peace agreement—one that was signed by Misuari and Fidel Ramos to much fanfare in 1996. Both led to armed confrontations that resulted in much death and suffering among civilians.

The government had also reportedly dangled a “final peace agreement” in 2003, this time to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), when it attacked the latter’s 200-hectare Buliok complex in Pikit, North Cotabato. The AFP itself admitted that the attack, and subsequent attacks, led to almost 200 deaths.

(Interestingly, it was then-Lt. Senior Grade Antonio Trillanes IV who exposed an “Operation Greenbase”, which he said was an AFP plan to attack the Buliok complex and conduct a series of bombings in Mindanao that was later blamed on the MILF. Today, look where Trillanes stands.)

One of the most serious and prolonged armed confrontations in Moro Mindanao in the last decade also occurred in the context of signing another peace agreement. In July 2008, the Arroyo government declared its commitment to sign the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) with the MILF. But local politicians like then-North Cotabato Vice Gov. Emmanuel Pinol mobilized paramilitary groups to campaign against the agreement. It was declared illegal by the Supreme Court. This led to a series of confrontations between MILF commanders and military and paramilitary groups. By 2009, about 600,000 civilians had been displaced—the second largest civilian displacement due to armed confrontation in the world.

In 2013, more than 100,000 civilians were likewise displaced when government troops, including SAF commandos, engaged MNLF fighters led by Ustadz Habier Malik who sought to hoist their flag in front of the Zamboanga City Hall. The international human rights group Human Rights Watch reported that government forces committed massive abuses, including prison mistreatment, torture and disregard for civilians. Again, the abuses were, for the most part, left unreported.

Beyond a few congressional investigations, government officials responsible for the outbreak of bloody wars—like then-Gen. Angelo Reyes in Basilan; 104th Brigade commander then-Col. Romeo Tolentino (who eventually commanded the entire Army before his retirement) in Jolo; then-Defense Secretary Reyes, again, in Pikit; Reyes again in Bicutan; Pinol and AFP officials after the MOA-AD junking and Zamboanga siege; and Presidents Arroyo and Aquino themselves—were never made to answer for their brutal actions.

Today, the Aquino administration seems hell-bent on absolving itself of any culpability in the Mamasapano carnage. And why not? Its predecessor got away with nine years of warmongering and countless human rights abuses (Arroyo is being held in “detention” for a different crime altogether).

This time, however, 44 young police commandos died. Their tragic stories were quickly laid out in public view by the major media networks and their sympathetic commentators, broadcasters, analysts and field reporters. Again, it was mostly alternative media, a few independent journalists, human rights activists and progressives, who worked to show a broader picture of the tragedy. The Moro deaths were, again, almost an afterthought.

But I am more optimistic today. In 2005, very few reports of what actually happened in Bicutan came out. Today, because of the magnitude of the issue, the culpability of the Aquino regime and even the clear involvement of the US government in the Mamasapano debacle (which mainstream media, to its credit, helped expose), more people outside Mindanao and Moro communities talk about the Moro people and their struggle for self-determination. Social media—that technological creature absent in many of the crises of the past decade—is still rife with Islamophobic comments, but I believe many are coming around. None is more indicative of this than the statements of the PNP Academy Alumni Association, which said that AFP’s current all-out war in Maguindanao is merely a diversionary tactic of the Aquino administration.

I hope that many will begin to realize that not only the 44 police commandoes, but also the 18 Moro fighters and at least four civilians, died because of the selfish designs of a President and his foreign patron.