COP21: Anger and Hope

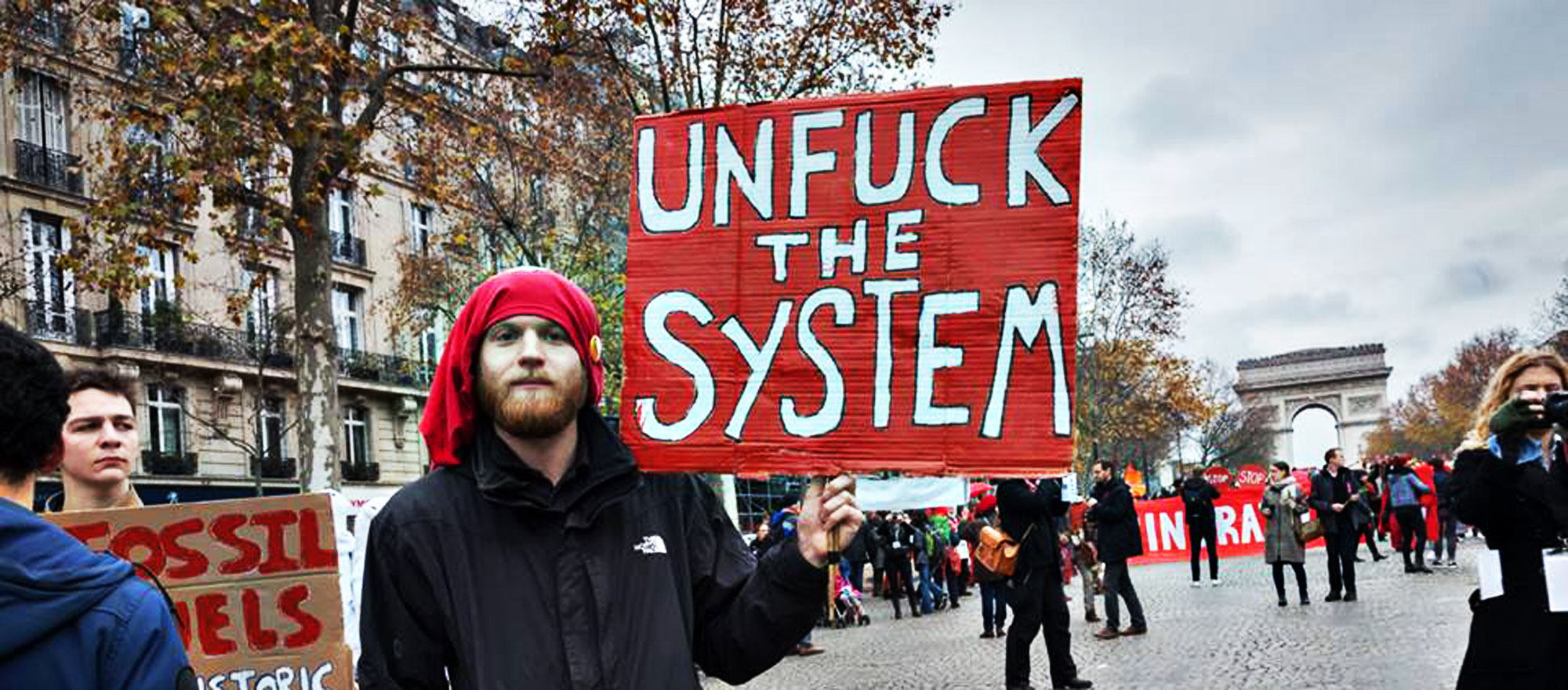

In what sense was COP21 historic? My experience of taking part in several protests at COP21 in Paris was truly inspiring. But the agreement itself is a source of frustration and anger.

Many have praised the COP21 Agreement as “historic,” but while I was following the conference’s closing discussions, I found myself wondering: historic in what sense? My experience of taking part in several protests at COP21 in Paris was truly inspiring. But the agreement itself is a source of frustration and anger.

The agreement does not provide guidelines that would ensure meaningful and desperately-needed government responses to the climate crisis. It also continues to leave the path open for neoliberal or free-market “solutions,” which involve privatizing public services, keeping down barriers to foreign investment, and the maintenance of vulnerable and deregulated economies. It means “business as usual” despite the climate crisis.

![]() These compromises are unacceptable. We are in a time when realists in the climate change movement recognize that an adequate response to the crisis will need to involve the public sector more than ever. Privatization has represented one of the most significant barriers to transition into renewable energy, not to mention being devastating for workers.

These compromises are unacceptable. We are in a time when realists in the climate change movement recognize that an adequate response to the crisis will need to involve the public sector more than ever. Privatization has represented one of the most significant barriers to transition into renewable energy, not to mention being devastating for workers.

It’s true that the agreement contains language recognizing the urgency of the crisis and obligations to the most vulnerable populations; it also contains gestures hinting at support for the burdens of renewable energy transition in developing countries. But this language is largely in the preamble, and not in the operative section of the agreement, so it’s just that: language. In the midst of a crisis that is undeniably planetary in scale, COP21 has given us more words and lesser commitment to take action as compared with previous climate change agreements.

Because of this, the Paris agreement lacks real, measurable and long-term mechanisms for attaining its supposed goal: sufficient reductions in emissions to prevent a 1.5? C increase in world temperature. Instead, reduction targets are only voluntary and, worse, the targets currently volunteered are projected to lead to an increase of 3? C or more. Such an increase would be disastrous for life in the planet. In fact, there is fear that small-island developing states would not survive the weather effects that may be unleashed as a result of such a temperature increase.

While developing countries face the greatest risk to climate change, at COP21, they remained bullied by the developed countries. Financial promises were used to win over some of the developing country governments, which represented big business interests, while the participation of people’s organizations were minimized. Organizations found opportunities to be heard only in a few smaller forums, while the business sector representatives were ever-present.

On top of that, developed countries imposed language in the agreement barring recognition of their primary role in bringing about the climate crisis and therefore shielding them from taking bolder action. The possibility of holding them accountable, which was discussed in the previous Durban talks, was enshrined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities” or CBDR-RC. But this has been made invalid by the COP 21 Paris Agreement. Developed and developing countries are therefore considered equally responsible for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

This represents a serious step backwards. After the landfall of Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda), which claimed more than 6,000 lives and which was one of the strongest typhoons in modern history, the discussion about the responsibility of developed countries for climate change cannot be avoided. This is especially true because experts project the continuation of extreme weather events in the future, and victims of Haiyan continue to wait for justice. These victims wait in devastated areas that still don’t have clean water and sanitation.

The Paris agreement also does not support “just transition” or the kind of renewable energy transitions that would protect workers against massive lay-offs and economic displacement. These are outcomes that the agreement only commits, to use its own words, to “taking into account.”

The agreement sets a “quantified goal from a floor of USD 100 billion” as a form of support for necessary energy transitions for developing countries. According to an estimate recognized by the United Nations, however, what is needed is at least ten times this amount, or USD 1,000 billion. This means that workers are in for a fight. Lack of sufficient support for just transition is one of the loopholes in the agreement that allow privatization and the further domination of other neoliberal policies, which would mean, among other things, worsening contractualization.

The Aquino government’s scheme to phase out jeepneys from the country’s roads, for example, will result in significant job loss and place more of the transportation sector under big corporate control (which, remember, has been a disaster for the MRT/LRT in terms of safety and cost to passengers). And while the phaseout is supposedly being done to fight pollution, the Aquino administration has chosen corporate control rather than a stricter emissions test system as the mechanism. Such measures will not likely represent a significant emissions improvement, especially when Aquino has just approved the construction of more coal-fired power plants and continues to allow the dumping of cars by the automobile industry into the country.

In another example, negative side effects of the renewable energy transition, land-grabbing in regions like the Visayas – but also in Brazil, West and Central Africa – continues to be driven by the foreign demand for biofuels.

A genuinely just transition would involve greater financial support from countries primarily responsible for the climate crisis, and the mobilization of citizens to democratize their governments and ensure commitment to both emissions reduction and the well-being of the workers and other marginalized sectors. Such an effort towards genuine democracy will clash with central elements of capitalism as we know it. So, in the face of the climate crisis, we have no choice but to commit to changing that system altogether.

If there’s anything to be hopeful about, it’s the response of the workers and the people’s organizations: trade unions, human rights activists, indigenous peoples, women, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and other populations most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Both inside and outside COP21, they aggressively put forth pro-worker and pro-people demands.

They recognize the need to go beyond, way beyond, COP21 and to pursue radical changes in the global economic system. Many among them recognize that the socio-economic system that caused the climate crisis is the very same system that will not accept even meager restrictions on its operations, and that system change is necessary if we are to stop climate change.

What COP21 provides is further evidence that the struggle for system change will have to be led by the marginalized sectors and their movements. For us in the labor movement, that means we have to bring the climate crisis issue into our efforts at educating, agitating and mobilizing workers – more swiftly and more purposefully.

We’ve already seen too many disasters in the Philippines, so we should all be aware that no less than our lives and livelihoods depend on it.