#MaryJaneLives

[cycloneslider id=”maryjanelives”] It was a uniquely amazing experience: thousands of people, anxiously awaiting the imminent execution of one of their own — Filipino migrant worker Mary Jane Veloso — and then being told that something unexpectedly good happened after all. She lived. The Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, had, at literally the last minute, decided to stay Mary […]

[cycloneslider id=”maryjanelives”]

It was a uniquely amazing experience: thousands of people, anxiously awaiting the imminent execution of one of their own — Filipino migrant worker Mary Jane Veloso — and then being told that something unexpectedly good happened after all. She lived.

The Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, had, at literally the last minute, decided to stay Mary Jane’s execution. The reasons were not clear at that moment. There were few details then to make sense of it. Of what came out, though, it is known that past midnight of April 29, Mary Jane was on her way to the execution site, wearing immaculate white (her last statement, perhaps, reiterating her innocence), preferring not to be blindfolded and wanting to face her executioners, when she was told that the execution would not push through. She was spared, while the eight others continued to face the firing squad. That Mary Jane survived that moment at all — being told she would die soon, then spared at literally the last minute — was a testament to her nerves steeled in half a decade on death row.

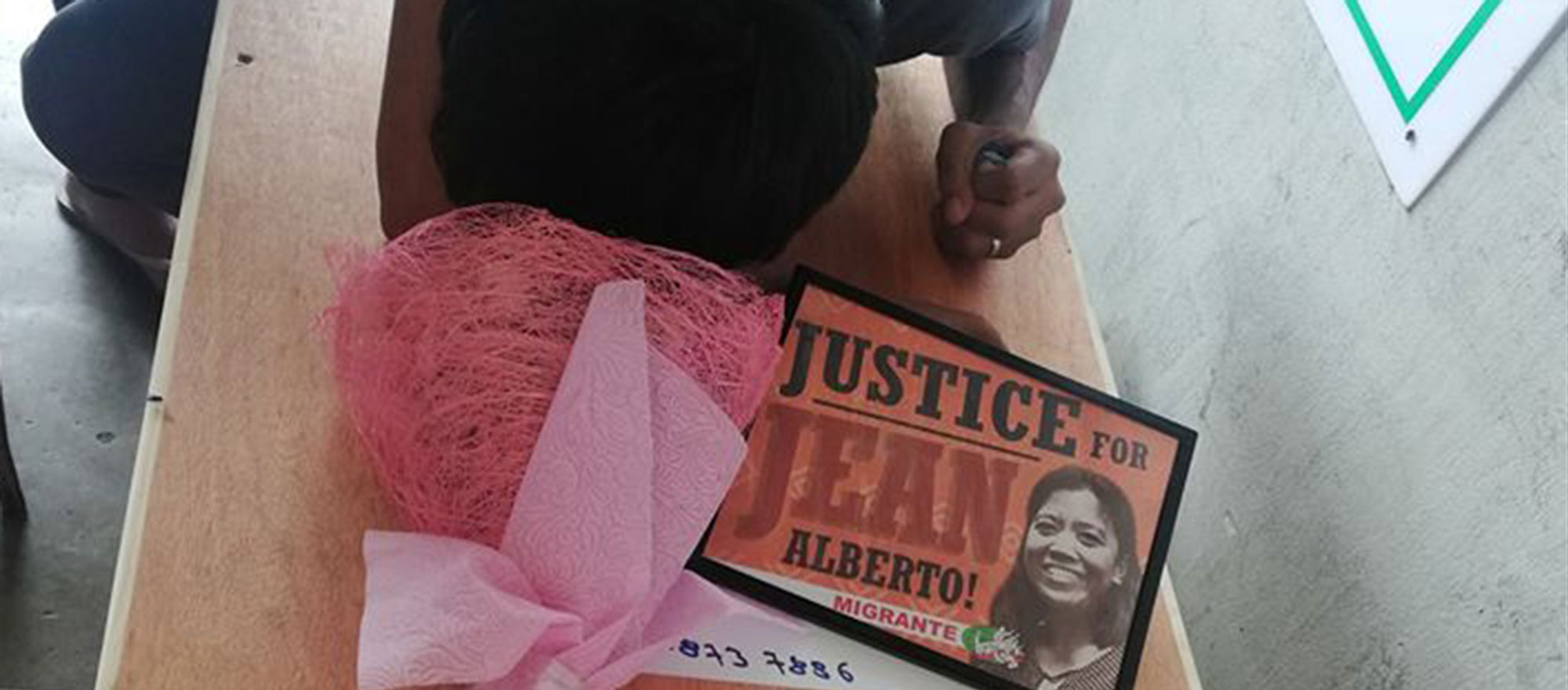

Nerves were likewise tested during the vigil near the Indonesian embassy in Makati City. The thousands of people gathered there, most of them ordinary folk, many seasoned activists from various sectors, merely awaiting confirmation of the execution. At around 8 PM, Mary Jane’s family members and lawyers communicated that the Indonesian attorney-general had ruled out any possibility of clemency. Philippine embassy officials told media that Mary Jane would be executed 9 PM, while Indonesian media reported that it was to happen at around 1 or 2 in the morning. When Migrante International’s chairperson, Garry Martinez, tearfully announced this, the activists wept, but they seethed, too, cursing at and tearing images of Widodo and Aquino, flinging their fists in the air like they had not done before.

Still, there was time, and, therefore, there was hope. There was a last-minute meeting between Widodo and Indonesian migrant groups. Church activists circulated the attorney-general’s number and urged those in vigil attendance to text the number. “Mercy is not weakness,” texted a few of them, referring to the attorney-general’s reported statement that granting clemency to Mary Jane and the others would be seen internationally as a sign of weakness and capitulation to outside pressure. Social media was abuzz with expressions of sadness, anger and pleads for mercy, while gatherings and vigils were also organized in many other areas within and outside the country.

They kept vigil as Mary Jane’s darkest hour neared. When the moment arrived — past 1 in the morning — the audience’s energy was mostly spent. Meanwhile, news from Indonesian media, picked up by Australian and other English-language media groups, began reporting that 8 of the 9 who were sentenced to die were executed, and that Mary Jane was granted a last-minute reprieve. By 1:40 AM, Martinez took the microphone and announced the good news. The crowd instantly erupted in cheers. People were weeping in joy, hugging each other, raising their fists in victory. “To the Department of Foreign Affairs (which earlier announced there was no hope for Mary Jane),” said youth leader Vencer Crisostomo of Anakbayan, “we say you are wrong! Mary Jane lives! We will bring you back home, Mary Jane. We will fight for it!”