Writing Behind Bars*

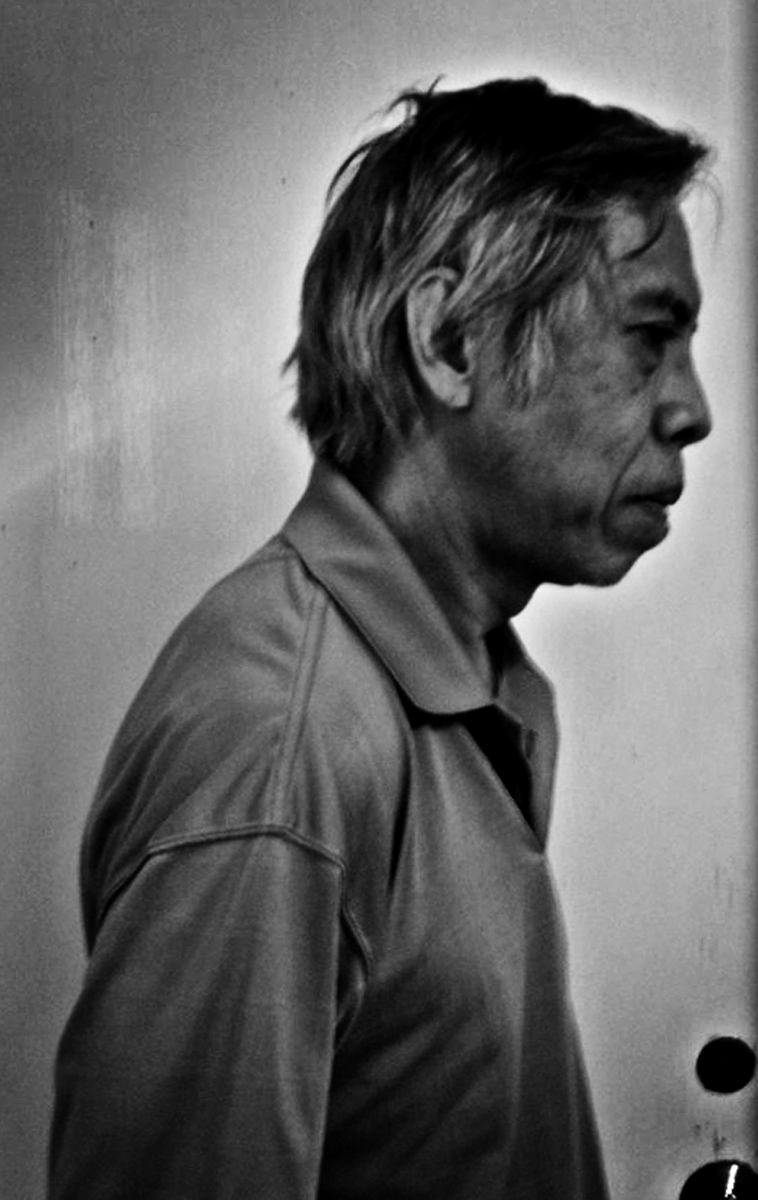

A 1989 review of a book of poems by then-and-now political prisoner Alan Jazmines, featuring poems on his encarceration and torture under the Marcos dictatorship.

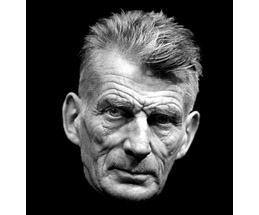

Prison writing is a genre with a long tradition. Among the notable practitioners of this writing are John Milton, who, incarcerated by the royalists, wrote his epic poems Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, and in the Philippines, Francisco Balagtas, who gave us Florante at Laura; Jose Rizal who wrote his Mi Ultimo Adios in Fort Santiago near the turn of the 20th century; and Amado Hernandez, whose prison poems in the 1950s were smuggled out on slips of newsprint by his wife, the actress Atang de la Rama.

Given that the Philippines has had thousands of political prisoners, the output has been prodigious. A Canadian editor put together in his 1988 anthology of Filipino poetry in English the works of Macario Tiu, Agustin Pagusara Jr., Edicio de la Torre, Felipe Granrojo (a pen name), Isagani Serrano, Mila Aguilar, Edgar Maranan, Jose Maria Sison, and Alan V. Jazmines. There are scores of writers whose works appear in other anthologies: Cesario Y. Torres, Jose F. Lacaba, Maria Lorena Barros, Francisco Rodrigo, Benigno Aquino Jr., Bienvenido Lumbera, Lilia Quindoza, Bonifacio Ilagan, Mano de Verdades Posadas (a pen name), Carlos Humberto (a pen name), Aida Santos, Romeo Dizon, and many others whose protest works will never be in the literary canon unless scholars adjust their formalist criteria and retrieve these works, which are reflexively shunted aside by the establishment.

As a teacher of literature, I see the necessity and value of collecting the works of Filipino writers, in whatever languages, that have an emancipatory thrust. Research on the underground press has yielded many such pieces, largely songs, poems, stories, plays, and expository material. Three long underground works written during the martial-law period were published in the 1980s: two novels, Hulagpos (To Break Free), by Mano de Verdades Posadas (1980), and Sebyo, by Carlos Humberto (1990); and a biography, Sa Tungki ng Ilong ng Kaaway: Talambuhay ni Tatang (Under the Enemy’s Nose: The Autobiography of Tatang (1988). These and the other unanthologized and unpublished works constitute together with the prison writings the struggle literature that, in turn, add up to revolutionary literature.

Moon’s Face is a remarkable addition to a growing genre. At this point, it may be useful to differentiate among the 80 poems (written in the early 1980s) and come up with a definition of the genre. Prison poetry is written in incarceration but it is not altogether about prison. The author who arranged the poems himself made sure, however, that prison life, from the time of his arrest on 12 May 1974, to the time of his release in early 1986, is rendered fully in more than 30 poems in the first part of the collection. When reading Topsy-turvy Ordeal, I cannot help but retrieve an entry from the Amnesty International report (1975) about the author:

Moon’s Face is a remarkable addition to a growing genre. At this point, it may be useful to differentiate among the 80 poems (written in the early 1980s) and come up with a definition of the genre. Prison poetry is written in incarceration but it is not altogether about prison. The author who arranged the poems himself made sure, however, that prison life, from the time of his arrest on 12 May 1974, to the time of his release in early 1986, is rendered fully in more than 30 poems in the first part of the collection. When reading Topsy-turvy Ordeal, I cannot help but retrieve an entry from the Amnesty International report (1975) about the author:

During the transfer (to a military “safehouse”) he was blind-folded and handcuffed and his guards beating him… He was then interrogated and tortured continuously for three months until July 1974… during the most of the three months, he was handcuffed with his hands over his head to bed posts day and night… on one occasion, he was thrown handcuffed into a swimming pool until he almost drowned. He was subjected repeatedly to the torture known as “San Juanico Bridge”… he vomited often during and after the beatings. His entire body grew swollen and areas of skin were stripped from his thighs…

This is how he remembered it all, years later:

Chained upside down like in a slaughter house

you were flailed inside-out

until your skin assumes

a darker version of the color of your blood

and flesh became the substitute for skin.

There is no room for despair or pessimism in his prison poems. He describes what is necessary “to maintain a fighting stance in whatever form they chose to mangle with your body and your mind.” Otherwise, “you would have turned into the opposite of yourself.” The poems attest to his staying whole and growing firmer in conviction.

The struggle continues, as it were, in prison:

we shall prove over and again that we are sharper than rock

and increasingly grow.

The enemy is in images of black:

we are faced with the black

of this steely apparatus

in this protracted war.

To cope with this, as in the title poem,

we have to calibrate

our sense and cross-

hairs of our nerves, finely

discern the white shadows of a false sun

widely veiling the furtive movements of black.

Indeed, you can imprison the revolutionary but not the revolution.

Having come to terms with the struggle in prison, the author shifts his focus to the outside world, glimpsed, to be sure, from behind bars, with bits and pieces derived from media, visitors and memory. The committed sensibility then takes over, and shapes the rest of the poems dealing with the events following the assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino Jr., the US military bases, the prostitutes and the Marian crusaders in Ermita, the dissembling politicians, and the Batasan elections, the police and salvagings, urban resistance, capitalism, fallen comrades, and the guerrilla war in the countryside.

It is only fitting that the revolutionary poet, now reunited with his comrades, ends with The Climb, where the “last stretch was longest and arched steepest against us,” and the outcome is not in question:

We gained height at the apex,

towering it.

The mountain sank at our feet

and the entire plains

rose before us

in historic splendor.

(1989)

* From the book Emergent Literature, Essays on Philippine Writing. UP Press. Diliman, Quezon City. 2001.